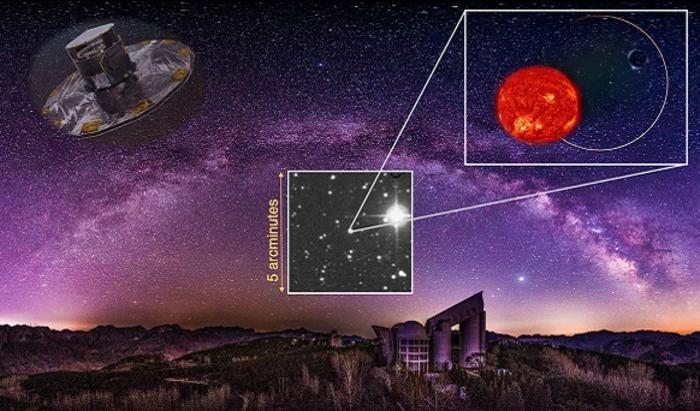

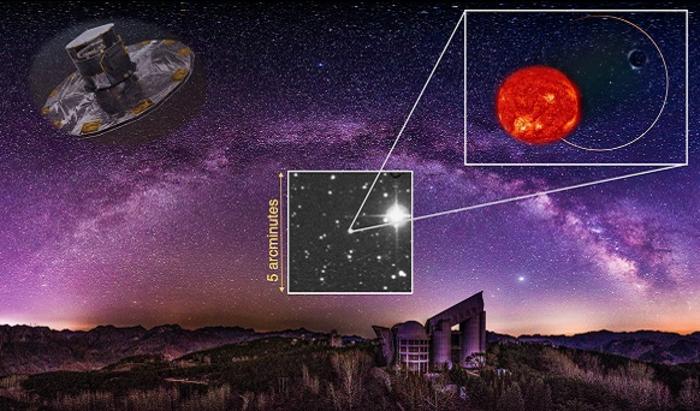

Astronomers using Gaia data have just found a low-mass black hole orbiting a companion star. Credit: WANG Song

Astronomers have discovered a light black hole that is a cosmic conundrum. Hypothetically, the masses of black holes could range from much less than a paper clip to at least tens of billions of times the mass of the Sun. But observations have revealed a strange lack of black holes between about two and five times the mass of the Sun. Right now, it’s unclear whether these mini black holes are just hard to detect or actually as rare as they seem.

Newly discovered black hole may provide clues. It falls right in the middle of the gap, weighing in at about 3.6 solar masses. A team of scientists found it thanks to a bulge companion, a red giant star located about 5,800 light-years from Earth. Although the star is only about 2.7 times the size of the Sun, it is about 13 times larger and 100 times brighter.

Discovery of a black hole

Using data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, which tracks the positions of more than a billion stars in our galaxy over time, astronomers spotted the red giant orbiting an invisible partner. Because Gaia mostly tracks proper motion—2D motion, or left, right, up, and down—scientists followed ground-based telescopes to measure the star’s motion toward and away from us.

This information revealed something unexpected: two objects, together called G3425, with a very wide circular orbit around each other.

Here’s why it’s weird. When the black hole formed, it would have rapidly lost mass during a supernova explosion. This weight loss should break the binary’s gravity.

“There’s a really basic idea of orbital mechanics that if a binary system loses half its mass, it becomes unbound,” Phil Plait, an astronomer who was not involved in the study, wrote in a paper. “In other words, both objects fly away.” While in this case the black hole’s weight loss wouldn’t be extreme enough to tear it apart entirely, it would have resulted in a very elongated orbit—not the near-circular one astronomers saw.

This also assumes that the supernova occurred uniformly. However, observations have shown that these explosions can be slightly one-sided, sending the remaining object careening into space. This would certainly explain why so few low-mass black holes are found – they can be torn away from their companion stars, left to wander the cosmic abyss alone and unseen. And that makes the unlikely cosmic duo G3425 that much more interesting.

Song Wang, an astronomer from the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences who co-led the study, suggests another possible explanation. G3425 may have started as a triple star system with two massive stars at the center and the red giant orbiting the pair. “The actual black hole [may have] formed as a result of an inner binary merger,” he says. “It is also possible that the invisible central object still contains two less massive compact objects.”

Curiouser and more curious

The researchers were tracking binary systems in which one member was a light black hole to test the idea that such systems might not even be possible. But now that they’ve demonstrated a way to identify low-mass black hole systems, future observations could provide clues about how common these objects are and how they might form.

Scientists deduced G3425 from Gaia observations of nearly 1.5 billion sources, but there are more than 100 billion stars in our galaxy. Wang says it hints that hundreds of other such systems may be out there just waiting to be found. Identifying and studying more of them, along with improving theories and simulations, could explain how these pairs evolved.

In his newsletter, Plait points out that this isn’t the first time scientists have noticed binary systems that shouldn’t exist. A separate Gaia study targeted binary systems containing stars like our Sun, along with dense stellar corpses called neutron stars, which can also form after the collapse of a massive star.

Neutron stars are so faint that they are extremely difficult to detect when they are alone. But by watching Sun-like stars wobble, the researchers were able to identify nearly two dozen dead stars that were invisibly pulling their brighter partners.

Again, it is unclear how these binaries exist.

“In principle, the progenitor of the neutron star should have become massive and interacted with the solar-type star during its late-stage evolution,” said the leader of that study, Kareem El-Badry, an assistant professor of astronomy at Caltech. and an assistant scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, in a press release. When that progenitor went supernova, it should have blasted the two stars in different directions.

“Clearly, we’re missing a piece here, and my gut feeling is that it’s the same piece in both stories,” Plait says. “Some factor in the way stars evolve in a binary is doing something unexpected, and it’s doing similar things for black holes and neutron stars in wide orbits around Sun-like stars.”